© 1918.

Henry Morgenthau

American Ambassador to Constantinople

1913-1916

CHAPTER XXVII

"I SHALL DO NOTHING FOR THE

ARMENIANS" SAYS THE GERMAN AMBASSADOR

Suppose that there is no phase of the Armenian

question which has aroused more interest than this: Had the Germans any part in it? To

what extent was the Kaiser responsible for the wholesale slaughter of this nation? Did the

Germans favour it, did they merely acquiesce, or did they oppose the persecutions?

Germany, in the last four years, has become responsible for many of the blackest pages in

history; is she responsible for this, unquestionably the blackest of all?

I presume most people will detect in the remarks of

these Turkish chieftains certain resemblances to the German philosophy of war. Let me

repeat particular phrases used by Enver and other Turks while discussing the Armenian

massacres: "The Armenians have brought this fate upon themselves." "They

had a fair warning of what would happen to them." "We were fighting for our

national existence ... .. We were justified, in resorting to any means that would

accomplish these ends." "We have no time to separate the innocent from the

guilty." "The only thing we have on our mind is to win the war."

These phrases somehow have a familiar ring, do they

not? Indeed, I might rewrite all these interviews with Enver, use the word Belgium in

place of Armenia, put the words in a German general's mouth instead of Enver's, and we

should have almost a complete exposition of the German attitude toward subject peoples.

But the teachings of the Prussians go deeper than this. There was one feature about the

Armenian proceedings that was new---that was not Turkish at all . For centuries the Turks

have ill-treated their Armenians and all their other subject peoples with inconceivable

barbarity. Yet their methods have always been crude, clumsy, and unscientific. They

excelled in beating out an Armenian's brains with a club, and this unpleasant illustration

is a perfect indication of the rough and primitive methods which they applied to the

Armenian problem. They have understood the uses of murder, but not of murder as a fine

art. But the Armenian proceedings of 1915 and 1916 evidenced an entirely new mentality.

This new conception was that of deportation. The Turks, in five hundred years, had

invented innumerable ways of physically torturing their Christian subjects, yet never

before had it occurred to their minds to move them bodily from their homes, where they had

lived for many thousands of years, and send them hundreds of miles away into the desert.

Where did the Turks get this idea? I have already described how, in 1914, just before the

European War, the Government moved not far from 100,000 Greeks from their age-long homes

along the Asiatic littoral to certain islands in the Aegean. I have also said that Admiral

Usedom, one of the big German naval experts in Turkey, told me that the Germans had

suggested this deportation to the Turks. But the all-important point is that this idea of

deporting peoples en masse is, in modern times, exclusively Germanic. Any one who reads

the literature of Pan-Germany constantly meets it. These enthusiasts for a German world

have deliberately planned, as part of their programme, the ousting of the French from

certain parts of France, of Belgians from Belgium, of Poles from Poland, of Slavs from

Russia, and other indigenous peoples from the territories which they have inhabited for

thousands of years, and the establishment in the vacated lands of solid, honest Germans.

But it is hardly necessary to show that the Germans have advocated this as a state policy;

they have actually been doing it in the last four years. They have moved we do not know

how many thousands of Belgians and French from their native land. Austria-Hungary has

killed a large part of the Serbian population and moved thousands of Serbian children into

her own territories intending to bring them up as loyal subjects of the empire. To what

degree this movement of populations has taken place we shall not know until the end of the

war, but it has certainly gone on extensively.

Certain German writers have even advocated the

application of this policy to the Armenians. According to the Paris Temps, Paul Rohrbach

"in a conference held at Berlin, some time ago, recommended that Armenia should be

evacuated of the Armenians. They should be dispersed in the direction of Mesopotamia and

their places should be taken by Turks, in such a fashion that Armenia should be freed of

all Russian influence and that Mesopotamia might be provided with farmers which it now

lacked." The purpose of all this was evident enough. Germany was building the Bagdad

railroad across the Mesopotamian desert. This was an essential detail in the achievement

of the great new German Empire, extending from Hamburg to the Persian Gulf. But this

railroad could never succeed unless there should develop a thrifty and industrious

population to feed it. The lazy Turk would never become such a colonist. But the Armenian

was made of just the kind of stuff which this enterprise needed. It was entirely in

accordance with the German conception of statesmanship to seize these people in the lands

where they had lived for ages and transport them violently to this dreary, hot desert. The

mere fact that they had always lived in a temperate climate would furnish no impediment in

Pan-German eyes. I found that Germany had been sowing those ideas broadcast for several

years; I even found that German savants had been lecturing on this subject in the East.

"I remember attending a lecture by a well-known German professor," an Armenian

tells me. "His main point was that throughout their history the Turks had made a

great mistake in being too merciful toward the non-Turkish population. The only way to

insure the prosperity of the empire, according to this speaker, was to act without any

sentimentality toward all the subject nationalities and races in Turkey who did not fall

in with the plans of the Turks."

The Pan-Germanists are on record in the matter of

Armenia. I shall content myself with quoting the words of the author of

"Mittel-Europa," Friedrich Naumann, perhaps the ablest propagator of Pan-German

ideas. In his work on Asia, Naumann, who started life as a Christian clergyman, deals in

considerable detail with the Armenian massacres of 1895-96. 1 need only quote a few

passages to show the attitude of German state policy on such infamies: "If we should

take into consideration merely the violent massacre of from 80,000 to 100,000

Armenians," writes Naumann, "we can come to but one opinion---we must absolutely

condemn with all anger and vehemence both the assassins and their instigators. They have

perpetrated the most abominable massacres upon masses of people, more numerous and worse

than those inflicted by Charlemagne on the Saxons. The tortures which Lepsius has

described surpass anything we have ever known. "What then prohibits us from falling

upon the Turk and saying to him: 'Get thee gone, wretch!'? Only one thing prohibits us,

for the Turk answers: 'I, too, I fight for my existence!'---and indeed, we believe him. We

believe, despite the indignation which the bloody Mohammedan barbarism arouses in us, that

the Turks are defending themselves legitimately, and before anything else we see in the

Armenian question and Armenian massacres a matter of internal Turkish policy, merely an

episode of the agony through which a great empire is passing, which does not propose to

let itself die without making a last attempt to save itself by bloodshed. All the great

powers, excepting Germany, have adopted a policy which aims to upset the actual state of

affairs in Turkey. In accordance with this, they demand for the subject peoples of Turkey

the rights of man, or of humanity, or of civilization, or of political liberty---in a

word, something that will make them the equals of the Turks. But just as little as the

ancient Roman despotic state could tolerate the Nazarene's religion, just as little can

the Turkish Empire, which is really the political successor of the eastern Roman Empire,

tolerate any representation of western free Christianity among its subjects. The danger

for Turkey in the Armenian question is one of extinction. For this reason she resorts to

an act of a barbarous Asiatic state; she has destroyed the Armenians to such an extent

that they will not be able to manifest themselves as a political force for a considerable

period. A horrible act, certainly, an act of political despair, shameful in its details,

but still a piece of political history, in the Asiatic manner. . . . In spite of the

displeasure which the German Christian feels at these accomplished facts, he has nothing

to do except quietly to heal the wounds so far as he can, and then to let matters take

their course. For a long time our policy in the Orient has been determined: we belong to

the group that protects Turkey, that is the fact by which we must regulate our conduct. .

. . We do not prohibit any zealous Christian from caring for the victims of these horrible

crimes, from bringing up the children and nursing the adults. May God bless these good

acts like all other acts of faith. Only we must take care that deeds of charity do not

take the form of political acts which are likely to thwart our German policy. The

internationalist, he who belongs to the English school of thought, may march with, the

Armenians. The nationalist, he who does not intend to sacrifice the future of Germany to

England, must, on questions of external policy, follow the path marked out by Bismarck,

even if it is merciless in its sentiments. . . . National policy: that is the profound

moral reason why we must, as statesmen, show ourselves indifferent to the sufferings of

the Christian peoples of Turkey, however painful that may be to our human feelings. . . .

That is our duty, which we must recognize and confess before God and before man. If for

this reason we now maintain the existence of the Turkish state, we do it in our own

self-interest, because what we have in mind is our great future. . . . On one side lie our

duties as a nation, on the other our duties as men. There are times, when, in a conflict

of duties, we can choose a middle ground. That is all right from a human standpoint, but

rarely right in a moral sense. In this instance, as in all analogous situations, we must

clearly know on which side lies the greatest and most important moral duty. Once we have

made such a choice we must not hesitate. William II has chosen. He has become the friend

of the Sultan, because he is thinking of a greater, independent Germany."

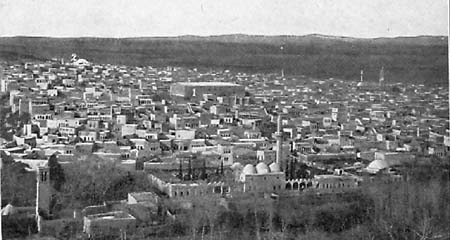

Fig. 52. VIEW OF URFA. One of the largest towns in Asia Minor

Fig. 53. A RELIC OF THE ARMENIAN MASSACRES AT ERZINGAN. Such

mementos are found all over Armenia

Such was the German state philosophy as applied to

the Armenians, and I had the opportunity of observing German practice as well. As soon as

the early reports reached Constantinople, it occurred to me that the most feasible way of

stopping the outrages would be for the diplomatic representatives of all countries to make

a joint appeal to the Ottoman Government. I approached Wangenheim on this subject in the

latter part of March. His antipathy to the Armenians became immediately apparent. He began

denouncing them in unmeasured terms; like Talaat and Enver, he affected to regard the Van

episode as an unprovoked rebellion, and, in his eyes, as in theirs, the Armenians were

simply traitorous vermin.

"I will help the Zionists," he said,

thinking that this remark would be personally pleasing to me, "but I shall do nothing

whatever for the Armenians."

Wangenheim pretended to regard the Armenian question

as a matter that chiefly affected the United States. My constant intercession in their

behalf apparently created the impression, in his Germanic mind, that any mercy shown this

people would be a concession to the American Government. And at that moment he was not

disposed to do anything that would please the American people.

"The United States is apparently the only

country that takes much interest in the Armenians," he said. "Your missionaries

are their friends and your people have constituted themselves their guardians. The whole

question of helping them is therefore an American matter. How, then, can you expect me to

do anything as long as the United States is selling ammunition to the enemies of Germany?

Mr. Bryan has just published his note, saying that it would be unneutral not to sell

munitions to England and France. As long as your government maintains that attitude we can

do nothing for the Armenians."

Probably no one except a German logician would ever

have detected any relation between our sale of war materials to the Allies and Turkey's

attacks upon hundreds of thousands of Armenian women and children. But that was about as

much progress as I made with Wangenheim at that time. I spoke to him frequently, but he

invariably offset my pleas for mercy to the Armenians by references to the use of American

shells at the Dardanelles. A coolness sprang up between us soon afterward, the result of

my refusal to give him "credit" for having stopped the deportation of French and

British civilians to the Gallipoli peninsula. After our somewhat tart conversation over

the telephone, when he had asked me to telegraph Washington that he had not hetzed the

Turks in this matter, our visits to each other ceased for several weeks.

There were certain influential Germans in

Constantinople who did not accept Wangenheim's point of view. I have already referred to

Paul Weitz, for thirty years the correspondent of the Frankfurter Zeitung, who probably

knew more about affairs in the Near East than any other German. Although Wangenheim

constantly looked to Weitz for information, he did not always take his advice. Weitz did

not accept the orthodox imperial attitude toward Armenia, for he believed that Germany's

refusal effectively to intervene was doing his fatherland everlasting injury. Weitz was

constantly presenting this view to Wangenheim, but he made little progress. Weitz told me

about this himself, in January, 1916, a few weeks before I left Turkey. I quote his own

words on this subject:

"I remember that you told me at the

beginning," said Weitz, "what a mistake Germany was making in the Armenian

matters. I agreed with you perfectly. But when I urged this view upon Wangenheim, he threw

me twice out of the room!"

Another German who was opposed to the atrocities was

Neurath, the Conseiller of the German Embassy. His indignation reached such a point that

his language to Talaat and Enver became almost undiplomatic. He told me, however, that he

had failed to influence them.

"They are immovable and are determined to

pursue their present course," Neurath said.

Of course no Germans could make much impression on

the Turkish Government as long as the German Ambassador refused to interfere. And, as time

went on, it became more and more evident that Wangenheim had no desire to stop the

deportations. He apparently wished, however, to reestablish friendly relations with me,

and soon sent third parties to ask why I never came to see him. I do not know how long

this estrangement would have lasted had not a great personal affliction befallen him. In

June, Lieutenant Colonel Leipzig, the German Military Attaché, died under the most tragic

and mysterious circumstances in the railroad station at Lule Bourgas. He was killed by a

revolver shot; one story said that the weapon had been accidentally discharged, another

that the Colonel had committed suicide, still another that the Turks had assassinated him,

mistaking him for Liman von Sanders. Leipzig was one of Wangenheim's intimate friends; as

young men they had been officers in the same regiment, and at Constantinople they were

almost inseparable. I immediately called on the Ambassador to express my condolences. I

found him very dejected and careworn. He told me that he had heart trouble, that he was

almost exhausted, and that he had applied for a few weeks' leave of absence. I knew that

it was not only his comrade's death that was preying upon Wangenheim's mind. German

missionaries were flooding Germany with reports about the Armenians and calling upon the

Government to stop the massacres. Yet, overburdened and nervous as Wangenheim was this

day, he gave many signs that he was still the same unyielding German militarist. A few

days afterward, when he returned my visit, he asked:

"Where's Kitchener's army?

"We are willing to surrender Belgium now,"

he went on. "Germany intends to build an enormous fleet of submarines with great

cruising radius. In the next war, we shall therefore be able completely to blockade

England. So we do not need Belgium for its submarine bases. We shall give her back to the

Belgians, taking the Congo in exchange."

I then made another plea in behalf of the persecuted

Christians. Again we discussed this subject at length.

"The Armenians,"' said Wangenheim,

"have shown themselves in this war to be enemies of the Turks. It is quite apparent

that the two peoples can never live together in the same country. The Americans should

move some of them to the United States, and we Germans will send some to Poland and in

their place send Jewish Poles to the Armenian provinces---that is, if they will promise to

drop their Zionist schemes."

Again, although I spoke with unusual earnestness,

the Ambassador refused to help the Armenians.

Still, on July 4th, Wangenheim did present a formal

note of protest. He did not talk to Talaat or Enver, the only men who had any authority,

but to the Grand Vizier, who was merely a shadow. The incident had precisely the same

character as his pro forma protest against sending the French and British civilians down

to Gallipoli, to serve as targets for the Allied fleet. Its only purpose was to put

Germans officially on record. Probably the hypocrisy of this protest was more apparent to

me than to others, for, at the very moment when Wangenheim presented this so-called

protest, he was giving me the reasons why Germany could not take really effective steps to

end the massacres. Soon after this interview, Wangenheim received his leave and went to

Germany.

Callous as Wangenheim showed himself to be, he was

not quite so implacable toward the Armenians as the German naval attaché in

Constantinople, Humann. This person was generally regarded as a man of great influence;

his position in Constantinople corresponded to that of Boy-Ed in the United States. A

German diplomat once told me that Humann was more of a Turk than Enver or Talaat. Despite

this reputation I attempted to enlist his influence. I appealed to him particularly

because he was a friend of Enver, and was generally looked upon as an important connecting

link between the German Embassy and the Turkish military authorities. Humann was a

personal emissary of the Kaiser, in constant communication with Berlin and undoubtedly he

reflected the attitude of the ruling powers in Germany. He discussed the Armenian problem

with the utmost frankness and brutality.

"I have lived in Turkey the larger part of my

life," he told me, "and I know the Armenians. I also know that both Armenians

and Turks cannot live together in this country. One of these races has got to go. And I

don't blame the Turks for what they are doing to the Armenians. I think that they are

entirely justified. The weaker nation must succumb. The Armenians desire to dismember

Turkey; they are against the Turks and the Germans in this war, and they therefore have no

right to exist here. I also think that Wangenheim went altogether too far in making a

protest; at least I would not have done so."

I expressed my horror at such sentiments, but Humann

went on abusing the Armenian people and absolving the Turks from all blame.

"It is a matter of safety," he replied;

"the Turks have got to protect themselves, and, from this point of view, they are

entirely justified in what they are doing. Why, we found 7,000 guns at Kadikeuy which

belonged to the Armenians. At first Enver wanted to treat the Armenians with the utmost

moderation, and four months ago he insisted that they be given another opportunity to

demonstrate their loyalty. But after what they did at Van, he had to yield to the army,

which had been insisting all along that it should protect its rear. The Committee decided

upon the deportations and Enver reluctantly agreed. All Armenians are working for the

destruction of Turkey's power and the only thing to do is to deport them. Enver is really

a very kind-hearted man; he is incapable personally of hurting a fly! But when it comes to

defending an idea in which he believes, he will do it fearlessly and recklessly. Moreover,

the Young Turks have to get rid of the Armenians merely as a matter of self-protection.

The Committee is strong only in Constantinople and a few other large cities. Everywhere

else the people are strongly 'Old Turk'. And these old Turks are all fanatics. These Old

Turks are not in favour of the present government, and so the Committee has to do

everything in their power to protect themselves. But don't think that any harm will come

to other Christians. Any Turk can easily pick out three Armenians among a thousand

Turks!"

Humann was not the only important German who

expressed this latter sentiment. Intimations began to reach me from many sources that my

"meddling" in behalf of the Armenians was making me more and more unpopular in

German officialdom. One day in October, Neurath, the German Conseiller, called and showed

me a telegram which he had just received from the German Foreign Office. This contained

the information that Earl Crewe and Earl Cromer had spoken on the Armenians in the House

of Lords, had laid the responsibility for the massacres upon the Germans., and had

declared that they had received their information from an American witness. The telegram

also referred to an article in the Westminster Gazette, which said that the German consuls

at certain places had instigated and even led the attacks, and particularly mentioned

Resler of Aleppo. Neurath said that his government had directed him to obtain a denial of

these charges from the American Ambassador at Constantinople. I refused to make such a

denial, saying that I did not feel called upon to decide officially whether Turkey or

Germany was to blame for these crimes.

Yet everywhere in diplomatic circles there seemed to

be a conviction that the American Ambassador was responsible for the wide publicity which

the Armenian massacres were receiving in Europe and the United States. I have no

hesitation in saying that they were right about this. In December, my son, Henry

Morgenthau, Jr., paid a visit to the Gallipoli peninsula, where he was entertained by

General Liman von Sanders and other German officers. He had hardly stepped into German

headquarters when an officer came up to him and said:

"Those are very interesting articles on the

Armenian question which your father is writing in the American newspapers."

"My father has been writing no articles,"

my son replied.

"Oh," said this officer, "just

because his name isn't signed to them doesn't mean that he is not writing them!"

Von Sanders also spoke on this subject.

"Your father is making a great mistake,"

he said, "giving out the facts about what the Turks are doing to the Armenians. That

really is not his business."

As hints of this kind made no impression on me, the

Germans evidently decided to resort to threats. In the early autumn, a Dr. Nossig arrived

in Constantinople from Berlin. Dr. Nossig was a German Jew, and came to Turkey evidently

to work against the Zionists. After he had talked with me for a few minutes, describing

his Jewish activities, I soon discovered that he was a German political agent. He came to

see me twice; the first time his talk was somewhat indefinite, the purpose of the call

apparently being to make my acquaintance and insinuate himself into my good graces. The

second time, after discoursing vaguely on several topics, he came directly to the point.

He drew his chair close up to me and began to talk in the most friendly and confidential

manner.

"Mr. Ambassador," he said, "we are

both Jews and I want to speak to you as one Jew to another. I hope you will not be

offended if I presume upon this to give you a little advice. You are very active in the

interest of the Armenians and I do not think you realize how very unpopular you are

becoming, for this reason, with the authorities here. In fact, I think that I ought to

tell you that the Turkish Government is contemplating asking for your recall. Your

protests for the Armenians will be useless. The Germans will not interfere for them and

you are just spoiling your opportunity for usefulness and running the risk that your

career will end ignominiously."

"Are you giving me this advice," I asked,

"because you have a real interest in my personal welfare?"

""Certainly," he answered; "all

of us Jews are proud of what you have done and we would hate to see your career end

disastrously."

"Then you go back to the German Embassy,"

I said, "and tell Wangenheim what I say---to go ahead and have me recalled. If I am

to suffer martyrdom, I can think of no better cause in which to be sacrificed. In fact, I

would welcome it, for I can think of no greater honour than to be recalled because I, a

Jew, have been exerting all my powers to save the lives of hundreds of thousands of

Christians."

Dr. Nossig hurriedly left my office and I have never

seen him since. When next I met Enver I told him that there were rumours that the Ottoman

Government was about to ask for my recall. He was very emphatic in denouncing the whole

story as a falsehood. "We would not be guilty of making such a ridiculous

mistake," he said. So there was not the slightest doubt that this attempt to

intimidate me had been hatched at the German Embassy.

Wangenheim. returned to Constantinople in early

October. I was shocked at the changes that had taken place in the man. As I wrote in my

diary, "he looked the perfect picture of Wotan." His face was almost constantly

twitching; he wore a black cover over his right eye, and he seemed unusually nervous and

depressed. He told me that he had obtained little rest; that he had been obliged to spend

most of his time in Berlin attending to business. A few days after his return I met him on

my way to Haskeuy; he said that he was going to the American Embassy and together we

walked back to it. I had been recently told by Talaat that he intended to deport all the

Armenians who were left in Turkey and this statement had induced me to make a final plea

to the one man in Constantinople who had the power to end the horrors. I took Wangenheim.

up to the second floor of the Embassy, where we could be entirely alone and uninterrupted,

and there, for more than an hour, sitting together over the tea table, we had our last

conversation on this subject.

"Berlin telegraphs me," he said,

"that your Secretary of State tells them that you say that more Armenians than ever

have been massacred since Bulgaria has come in on our side."

"No, I did not cable that," I replied.

"I admit that I have sent a large amount of information to Washington. I have sent

copies of every report and every statement to the State Department. They are safely lodged

there, and whatever happens to me, the evidence is complete, and the American people are

not dependent on my oral report for their information. But this particular statement you

make is not quite accurate. I merely informed Mr. Lansing that any influence Bulgaria

might exert to stop the massacres has been lost, now that she has become Turkey's

ally."

We again discussed the deportations.

"Germany is not responsible for this,"

Wangenheim said.

"You can assert that to the end of time,"

I replied, "but nobody will believe it. The world will always hold Germany

responsible; the guilt of these crimes will be your inheritance forever. I know that you

have filed a paper protest. But what does that amount to? You know better than I do that

such a protest will have no effect. I do not claim that Germany is responsible for these

massacres in the sense that she instigated them. But she is responsible in the sense that

she had the power to stop them and did not use it. And it is not only America and your

present enemies that will hold you responsible. The German people will some day call your

government to account. You are a Christian people and the time will come when Germans will

realize that you have let a Mohammedan people destroy another Christian nation. How

foolish is your protest that I am sending information to my State Department. Do you

suppose that you can keep secret such hellish atrocities as these? Don't get such a silly,

ostrich-like thought as that---don't think that by ignoring them yourselves, you can get

the rest of the world to do so. Crimes like these cry to heaven. Do you think I could know

about things like this and not report them to my government? And don't forget that German

missionaries, as well as American, are sending me information about the Armenians."

"All that you say may be true," replied

the German Ambassador, "but the big problem that confronts us is to win this war.

Turkey has settled with her foreign enemies; she has done that at the Dardanelles and at

Gallipoli. She is now trying to settle her internal affairs. They still greatly fear that

the Capitulations will again be forced upon them. Before they are again put under this

restraint, they intend to have their internal problems in such shape that there will be

little chance of any interference from foreign nations. Talaat has told me that he is

determined to complete this task before peace is declared. In the future they don't intend

that the Russians shall be in a position to say that they have a right to intervene about

Armenian matters because there are a large number of Armenians in Russia who are affected

by the troubles of their coreligionists in Turkey. Giers used to be doing this an the time

and the Turks do not intend that any ambassador from Russia or from any other country

shall have such an opportunity in the future. The Armenians anyway are a very poor lot.

You come in contact in Constantinople with Armenians of the educated classes, and you get

your impressions about them from these men, but all the Armenians are not of that type.

Yet I admit that they have been treated terribly. I sent a man to make investigations and

he reported that the worst outrages have not been committed by Turkish officials but by

brigands."

Wangenheim again suggested that the Armenians be

taken to the United States, and once more I gave him the reasons why this would be

impracticable.

"Never mind all these considerations," I

said. "Let us disregard everything---military necessity, state policy, and all

else---and let us look upon this simply as a human problem. Remember that most of the

people who are being treated in this way are old men, old women, and helpless children.

Why can't you, as a human being, see that these people are permitted to live? "

"At the present stage of internal affairs in

Turkey," Wangenheim replied, "I shall not intervene."

I saw that it was useless to discuss the matter

further. He was a man who was devoid of sympathy and human pity, and I turned from him in

disgust. Wangenheim rose to leave. As he did so he gave a gasp, and his legs suddenly shot

from under him. I jumped and caught the man just as he was falling. For a minute he seemed

utterly dazed; he looked at me in a bewildered way, then suddenly collected himself and

regained his poise. I took the Ambassador by the arm, piloted him down stairs, and put him

into his auto. By this time he had apparently recovered from his dizzy spell and he

reached home safely. Two days afterward, while sitting at his dinner table, he had a

stroke of apoplexy; he was carried upstairs to his bed, but he never regained

consciousness. On October 24th, I was officially informed that Wangenheim. was dead. And

thus my last recollection of Wangenheim is that of the Ambassador as he sat in my office

in the American Embassy, absolutely refusing to exert any influence to prevent the

massacre of a nation. He was the one, and his government was the one government, that

could have stopped these crimes, but, as Wangenheim told me many times, "our one aim

is to win this war."

Fig. 54. THE FUNERAL OF BARON

VON WANGENHEIM. The German Ambassador to Turkey. Mr. Morgenthau (in evening dress) is

walking with Enver Pasha. Immediately in front, of them is Talaat Pasha.A few days afterward official Turkey and the diplomatic force paid their

last tribute to this perfect embodiment of the Prussian system. The funeral was held in

the garden of the German Embassy at Pera. The inclosure was filled with flowers.

Practically the whole gathering, excepting the family and the ambassadors and the Sultan's

representatives, remained standing during the simple but impressive ceremonies. Then the

procession formed; German sailors carried the bier upon their shoulders, other German

sailors carried the huge bunches of flowers, and all members of the diplomatic corps and

the officials of the Turkish Government followed on foot.

The Grand Vizier led the procession; I walked the

whole way with Enver. All the officers of the Goeben and the Breslau, and all the German

generals, dressed in full uniform, followed. It seemed as though the whole of

Constantinople lined the streets, and the atmosphere had some of the quality of a holiday.

We walked to the grounds of Dolma Bagtche, the Sultan's Palace, passing through the gate

which the ambassadors enter when presenting their credentials. At the dock a steam launch

lay awaiting our arrival, and in this stood Neurath, the German Conseiller, ready to

receive the body of his dead chieftain. The coffin, entirely covered with flowers, was

placed in the boat. As the launch sailed out into the stream Neurath, a six-foot Prussian,

dressed in his military uniform, his helmet a waving mass of white plumes, stood erect and

silent. Wangenheim was buried in the park of the summer embassy at Therapia, by the side

of his comrade Colonel Leipzig. No final resting-place would have been more appropriate,

for this had been the scene of his diplomatic successes, and it was from this place that,

a little more than two years before, he had directed by wireless the Goeben and the

Breslau, and safely brought them into Constantinople, thus making it inevitable that

Turkey should join forces with Germany, and paving the way for all the triumphs and all

the horrors that have necessarily followed that event. |

Chapter Twenty-Five: Enver again moves for peace.